PFAS, often called “forever chemicals,” remain among the most important challenges in environmental and human health research. Their presence in food, water, air, and consumer products has recently pushed scientists and regulators to refine how human exposure is measured, modelled, and managed. At the international conference PFAS – Challenges and Scientific Perspectives in Human Health Risk Assessment held in Berlin 8th-10th October this year, experts from leading European institutions and universities gathered to discuss recent advances and remaining obstacles in understanding how PFAS affect human health. What emerged was a shared understanding that assessing PFAS risk means rethinking how exposure, toxicology, and environmental data are connected.

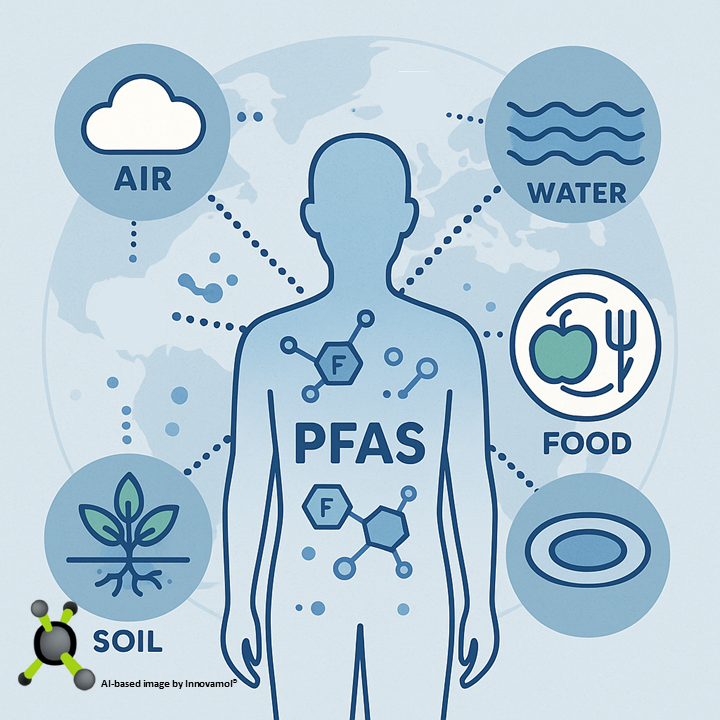

The traditional approach to risk assessment, focused on isolated measurements and individual substance, is giving way to a broader and more systemic view. PFAS act as families of related compounds that move across environmental media, i.e. air, water, soil, and food, forming a network of exposure pathways. Analytical advances now make it possible to detect them at extraordinarily low concentrations, yet the real challenge lies not in finding them but in interpreting what these traces means for human health. Scientific rigour must therefore be coupled with contextual understanding: how people live, eat, and interact with their environment determines how exposure is experienced.

Thus, regulatory frameworks are adapting to this reality. Rather than relying on rigid thresholds, decision-makers are exploring dynamic systems that combine scientific evidence with technical and social feasibility. In other words, effective limits must not only be defensible but also practical. This pragmatic approach represents a growing maturity in environmental governance: progress depends as much on cross-disciplinary collaboration as on analytical innovation. It is interesting to see therefore that the dialogue between science and policy is becoming central to ensuring that protective measures remain both credible and achievable.

Environmental research adds another layer of complexity. PFAS behave differently depending on the properties of soil, plant species, and local climate. The way they are transferred through ecosystems determines whether they remain confined to soil or enter the food chain. As a consequence, by understanding these mechanisms, scientists can advise on agricultural practices, land use, and monitoring strategies that prevent contamination before it occurs. This shift from retrospective detection to proactive management, illustrates how environmental science is becoming a tool for prevention rather than merely observation.

In humans, long-term biomonitoring provides a similarly complex picture. Concentrations of legacy PFAS have fallen substantially over the past decades, demonstrating that regulatory measures can succeed. Yet new, shorter-chain and ultra-short-chain compounds are appearing more frequently and demand careful study. Their differing persistence and biological behaviour show that substitution, if not guided by foresight, can perpetuate the same risks under new forms. The key lesson is that chemical management must evolve from replacement to redesign, thus anticipating consequences rather than reacting to them.

Recent studies on human kinetics are also changing how exposure is understood. Not all PFAS persist indefinitely; some are cleared from the body within days, others remain for years. Recognising this diversity allows for more accurate modelling of health effects and more targeted medical responses. Such insights bring together toxicology, physiology, and exposure science into a unified framework, which is an essential step towards realistic, human-centred risk assessment.

Among the emerging concerns, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) stands out as a particularly instructive case. Formed through the breakdown of refrigerants and certain pesticides, it is highly mobile and virtually non-degradable. Its growing presence in rainwater and groundwater exemplifies how chemical processes connect distant parts of the environment: what begins in the atmosphere eventually returns to the ground. Because TFA cannot be removed effectively through conventional water treatment, mitigation must begin at the source. This shift from remediation to prevention marks a fundamental reorientation of environmental policy.

Across the discussions, one idea connected all perspectives: the science of risk assessment is moving from counting contaminants to understanding systems. Progress depends less on producing more measurements than on linking the evidence we already have into coherent, predictive models. The future lies in connecting exposure data, toxicological knowledge, and digital tools to anticipate risk before harm occurs.

For Innovamol, these developments point to the direction of integrating analytical precision with computational and predictive modelling on data to support more adaptive, evidence-based decisions. PFAS are not simply a chemical challenge but a mirror reflecting the evolution of environmental health itself: towards data integration, foresight, and shared responsibility.

“We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them” – Albert Einstein