In an era where innovation intersects with our daily diets, the term “novel foods” frequently emerges at the forefront of food science discussions. However, with the growing number of unconventional foods on our tables, how can we distinguish between the truly “novel” and the simply new or exotic?

In the European Union, novel foods is defined food that had not been significantly consumed by humans in the EU prior to May 15, 1997. A significant milestone in EU was reached in 2015, the date on which the new novel food regulation introduced a centralised assessment and authorisation procedure (Regulation 2015/2283) and 2018 when this new regulation took effect with the Commission responsible for authorising novel foods after an EFSA safety evaluation. This definition covers a wide range of foods, including those that are traditionally consumed outside of the EU as well as newly created, developed foods that are produced using cutting-edge technologies and production techniques. Examples include food made using novel production techniques like UV-treated milk, cultivated meat, as well as agricultural such as chia seeds (Salvia hispanica) and krill oil from Euphausia superba.

Determining whether a food is novel or not is not trivial at all and requires a collection of lot of data. For example, leaves, fruits, seeds and oil of drumstick tree (Moringa oleifera) are to be considered NOT novel in food since, according to the information available to the EU Member States’ competent authorities, this product was used for human consumption to a significant degree within the Union before 15 May 1997. Thus, it is not considered to be ‘novel’ according to the provisions of the Novel Food Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 and its access to the market is not subject to the pre-market authorisation in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2015/2283.

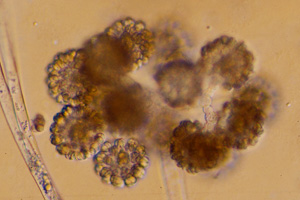

On the other hand, an example of novel food is lycopene derived from the fungus Blakeslea trispora. Lycopene, a naturally occurring carotenoid, is commonly found in tomatoes and other red fruits and vegetables. It is widely recognized for its antioxidant properties and potential health benefits. However, the lycopene sourced from Blakeslea trispora represents a significant innovation due to the novel method of production and it has been authorized in the EU as a novel food. This authorization means that before it was approved, the safety and efficacy of this lycopene source went through rigorous evaluation by the European Food Safety Authority to ensure it meets all health and safety standards set forth by Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. The process involves a thorough assessment of the production process, potential health effects, and nutritional impact.

Another example includes the seeds of Salvia hispanica, commonly known as chia seeds, which lately have gained significant popularity. Chia seeds were traditionally consumed in regions outside the EU and have been introduced to the European market relatively recently. Their classification as a novel food required comprehensive data on their historical consumption, nutritional content, and safety to be submitted and reviewed before they could be freely marketed within the EU.

Another interesting case is when different portions from the same source can have a different classification. For instance, hen-of-the-woods mushroom (Grifola frondosa) have dehydrated mycelium powder that are considered novel food while fruit bodies are not.

These examples represent the diverse range of products that fall under the novel food category, encompassing both innovative production methods and the introduction of traditional foods to new markets. This rigorous regulatory framework ensures that all novel foods in the EU are safe for consumption and beneficial to the public. More detailed information are available on the EU Novel Food Catalogue.

Distinguishing novel foods from non-novel ones is not a simple task as it requires extensive data collection, which remains a powerful tool for gathering essential information. Furthermore, the systematic organisation of this data is essential because it helps regulatory agencies in categorising foods in response to upcoming innovations and new challenges. This meticulous organisation of scientific data promotes innovation while preserving public health by guaranteeing that novel foods are appropriately assessed before being safely released to market.

“It is not the strongest of the species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change” – Charles Darwin